Three films from demonstrations in Syria yesterday. People protested in the suburbs of Damascus, Hama, Dera’a, the Kurdish north east, the desert town Raqqa and elsewhere. The first film shows a large crowd in Lattakia chanting ash-sha’ab yureed isqaat al-nizam – The People Want the Fall of the Regime. No reservations there. The second film shows security forces firing live ammunition at protestors in Homs. The third is Tartus. They’re chanting bi-rooh bi-dam nafdeek ya Dara’a – With Our Souls and Blood We Sacrifice for you, O Dara’a.

Category: Syria

Cage and Wave

This interview with Syria Comment’s Joshua Landis is well worth watching for background on Syria’s sectarian divisions and their influence on current events. I agree with most of what he says but I differ with his interpretation.

Two basic points of Syrian history come through very clearly. Firstly, Syria is not a unified nation in the way that Egypt is. There has been some form or other of centralised control in the Nile valley for thousands of years. Syria’s geography and demography – it’s a country of mountains, competing market cities and desert oases – means that power in Syria has always been much more divided, and that Syrians would feel more at home in an all-encompassing nation larger than the borders drawn by imperialists. Landis points out that in Syria’s brief democracy (the late 40s and early 50s) not one political party accepted the country’s borders. They sought instead either a unified pan-Arab state or a restitution of Bilad ash-Sham, the zone of enormous diversity between the Taurus mountains, the southern desert and the Euphrates river which nevertheless constitutes one market area and enjoys a common Levantine culture. Bilad ash-Sham is sliced today into Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine-Israel, and a sliver of Turkey.

Secondly, Landis identifies the crucial power division determining politics in contemporary Syria. The pre-police state parliament was dominated by the urban Sunni merchant class, the traditional elite. The army which would soon make the parliament irrelevant was inherited from the French occupation. Partly because the wealthier classes shied away from the army, but mainly for the usual divide-and-rule reasons, the French built a military of minorities – Alawis, Christians, Druze, and marginalised rural Sunnis. The victory of the military over the parliament, and of the military wing of the Ba’ath party over all other parties, was a victory of the countryside over the city, of the periphery over the centre, of sectarian minorities over the Sunni majority. The Ba’ath years therefore oversaw a social revolution in the sense that previously distanced and despised rural classes moved to the cities and entered elites.

Dinosaur in Denial

Until recently it seemed that Syria, along with wealthy Saudi Arabia, was the state least likely to fall to the revolutionary turmoil sweeping the Arab region.

Until recently it seemed that Syria, along with wealthy Saudi Arabia, was the state least likely to fall to the revolutionary turmoil sweeping the Arab region.

The first reason for the Asad regime’s seeming stability is Syrian fear of sectarian chaos. Beyond the Sunni Arab majority, Syria includes Alawis (most notably the president and key military figures), Christians, Ismailis, Druze, Kurds and Armenians, as well as Palestinian and Iraqi refugees. The state has achieved a power balance between the minorities and rural Sunnis while building an alliance with the urban Sunni business class. This means that Syria is the best place in the Middle East to belong to a religious minority, certainly better than in ‘liberated’ Iraq or in the Jewish state, and for a long time domestic peace under authoritarianism has looked more attractive than the neighbouring sectarian and strife-torn ‘democracies’ in Lebanon and Iraq (the American dismantling of the Iraqi state provided a serious blow to Arab democratic aspirations, neo-con fantasies notwithstanding).

Anger in Syria

Syrian security forces open fire on protesters

Syrian security forces are reported to be cracking down hard on anti-government protesters across the country.

Witnesses say at least 20 have been killed on Friday, the day activists were calling the ‘Day of Dignity’.

Al Jazeera’s Zeina Khodr has this exclusive report from the city of Dara’a.

Syrian Bloodbath

Some (I hope exaggerated) reports say that well over a hundred people were killed in the southern Syrian city of Dera’a yesterday. And after Friday prayers today, enraged Syrians took to the streets in nearby Sunamayn, in central and suburban Damascus, in towns such as Tell and Ma’adumiyeh in the Damascus countryside, and in the cities of Homs, Hama and Lattakiya. They chanted “God, Syria, Freedom – That’s All,” and “With our Souls and Blood We Sacrifice for You, O Dera’a.” And they did sacrifice; reports suggest that many more were killed and injured by the state’s bullets this afternoon.

Some (I hope exaggerated) reports say that well over a hundred people were killed in the southern Syrian city of Dera’a yesterday. And after Friday prayers today, enraged Syrians took to the streets in nearby Sunamayn, in central and suburban Damascus, in towns such as Tell and Ma’adumiyeh in the Damascus countryside, and in the cities of Homs, Hama and Lattakiya. They chanted “God, Syria, Freedom – That’s All,” and “With our Souls and Blood We Sacrifice for You, O Dera’a.” And they did sacrifice; reports suggest that many more were killed and injured by the state’s bullets this afternoon.

The officially-sanctioned chants usually heard in Syria promote sacrifice for President Bashaar al-Asad. Today a group of pro-regime demonstrators rather lamely replaced Freedom with Bashaar, as in “God, Syria, Bashaar – That’s All.” But it doesn’t work any more. Bashaar, previously perceived by many as innocent of his father’s regime’s crimes, now has blood on his hands. His name sounds like the antithesis of freedom.

Syria Shakes

A few weeks ago fifteen children were arrested in the southern Syrian city of Dera’a for writing revolutionary slogans on walls. This led to a series of demonstrations calling for the children’s release, the sacking of local officials, and an end to the decades-long state of emergency. Last Friday security forces opened fire on protestors, killing five people. Predictably, state violence redoubled the people’s rage. A Ba’ath Party office was burned and a phone company belonging to the president’s corrupt cousin Rami Makhlouf was attacked. Inspired by Tahreer Square and Pearl Roundabout, protestors then set up tents beside Dera’a’s Omari mosque and stated their intention to stay until their demands were met. Last night security forces attacked the mosque, killing six people.

Now Syria?

Syriacomment‘s Joshua Landis on dramatic events in Syria:

Momentum is building for the opposition. The demonstrations are getting bigger with each day. They started out gathering between 100 to 300. Today’s demonstration was well over 1,000 in Deraa. The New York Times is reporting that 20,000 joined the funeral march in Deraa. The killing of four in Deraa is new. Many Syrians claim that this is the first time President Assad has drawn blood with the shooting of demonstrators. The Kurdish intifada of 2004 in the Jazeera ended with the death of many but that occurred following the successful constitutional referendum in Iraq and was blamed on external factors. To many Syrians, this time seems different.

Syria Speeding Up

Three weeks ago I wrote that Syria was not about to experience a popular revolution. Although I’m no longer sure of anything after the events in Tunisia and Egypt (and Libya, Algeria, Jordan, Yemen and Bahrain) – and although it’s made me unpopular in certain quarters – I’m sticking to my original judgement. No revolution in Syria just yet.

Until a month ago, I would have have agreed with Joshua Landis (quoted here) that many, perhaps a comfortable majority of Syrians were not particularly interested in ‘democracy.’ Before either I or Landis is accused of orientalism, let me say that human and civil rights are not identical with democracy. Any Syrian who knows he’s alive wants his (or her) human and civil rights respected, but many fear that ‘democracy’ would lead to sectarian fragmentation. This is an entirely logical fear: the ‘democracies’ to the west and east of Syria – Lebanon and Iraq – are strife-torn sectarian democracies. Sectarian identification remains a problem in Syria. A freedom-loving Alawi friend of mine was put off the failed ‘day of rage’ facebook group because he found so many anti-Alawi comments posted there. Other Syrians were put off when they realised that many of the posts came from Hariri groups in Lebanon.

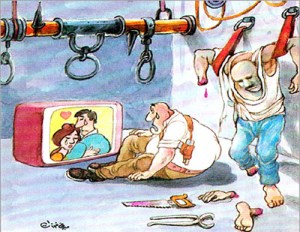

Breaking Knees

Zakaria Tamer’s “Breaking Knees” tugs us rushing straight into the Big Topics: religion, politics, sex and death. It deals with imprisonment, literal and figurative, its characters entrapped in unhappy marriages and by their personal inadequacies, ignorances and fears, as well as by dictatorship, bureaucracy and corrupt tradition. It sounds grim, but “Breaking Knees” is a very funny book.

Tamer is a well-known Syrian journalist and writer of children’s books. His literary reputation, however, rests on his development of the very short story (in Arabic, al-qissa al-qasira jiddan), of which there are 63 here. Each is a complex situational study, a flash of life or nightmare, each with at least one beginning, middle and end. Some are as clear as day; some are seriously puzzling. Some are no more than extended, taboo-breaking jokes.

It’s certainly satire. Tamer uses an elegant, euphemistic language (referring, for instance, to “that which men have, but not women”) to tell some very plain tales. Delicious irony abounds. In bed an adulterous woman begs her lover “not to soil the purity of her ablutions.” In the street afterwards she frowns at a woman without a headscarf and says “in a voice full of sadness that immoral behaviour had become widespread.”