This review of miriam cooke’s new book was published at the Guardian.

Syria’s revolution triggered a volcano of long-repressed thought and emotion in cultural as well as political form. Independent newspapers and radio stations blossomed alongside popular poetry and street graffiti. This is a story largely untold in the West. Who knew, for instance, of the full houses, despite continuous bombardment, during Aleppo’s December 2013 theatre festival?

“Dancing in Damascus” by Arabist and critic miriam cooke (so she writes her name, uncapitalised) aims to fill the gap, surveying responses in various genres to revolution, repression, war and exile.

Dancing is construed both as metaphor for collective solidarity and debate – as Emma Goldman said, “If I can’t dance, it isn’t my revolution” – and as literal practice. At protests, Levantine dabke was elevated from ‘folklore’ to radical street-level defiance, just as popular songs were transformed into revolutionary anthems.

Cooke’s previous book “Dissident Syria” examined the regime’s pre-2011 attempts to defuse oppositional art while giving the impression of tolerance. The regime would fund films for international screening, for instance, but ban their domestic release.

“Dancing in Damascus” describes how culture slipped the bounds of co-optation. Increasingly explicit prison novels and memoirs anticipated the uprising. Once the protests erupted, ‘artist-activists’ engaged in a “politics of insult” and irony. Shredding taboos, the Masasit Matte collective’s ‘Top Goon’ puppet shows, Ibrahim Qashoush’s songs and Ali Farzat’s cartoons targeted Bashaar al-Assad specifically. “The ability to laugh at the tyrant and his henchmen,” writes cooke, “helps to repair the brokenness of a fearful people.”

As the repression escalated, Syrians posted atrocity images in the hope they would mobilise solidarity abroad. This failed, but artistic responses to the violence helped transform trauma into “a collective, affective memory responsible to the future”.

Explicit representations of “brute physicality and raw emotion”, from mobile phone footage to Samar Yazbek’s literary reportage, soon gave way to formal experimentation. Notable examples include “Death is Hard Work”, Khaled Khalifa’s Faulknerian novel of a deferred burial, the ‘bullet films’ of the Abounaddara Collective, and Azza Hamwi’s ironic short “Art of Surviving”, about a man who turns spent ordinance into heaters, telephones, even a toilet. “We didn’t paint it,” he tells the camera, “so it stays as it arrived from Russia especially for the Syrian people.”

This section also covers full-length films such as “Return to Homs”, which follows the transformation of Abdul-Basit Sarut from star goalkeeper to protest leader to resistance fighter.

Cooke’s consideration of the role of social media is better informed than the somewhat superficial journalistic takes on the cyber aspects of the Arab Spring which filled commentary in 2011. The internet provides activists anonymity and therefore relative safety. It also offers a space in which to display and preserve art, even while Syria’s physical heritage, from Aleppo’s mosques to Palmyra’s temples, is demolished by regime bombs and jihadist vandalism. Online gallery sites archive the uprising’s creative breadth and complexity. One such is the Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution, whose multimedia approach sometimes “connects specific elements within each genre to produce a film about the process of painting that responds to music.”

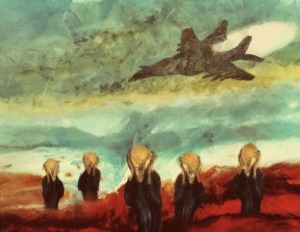

Certain digital images ‘aestheticise’ sites of destruction in order to both lament and humanise the war. The best known are works by Tammam Azzam which superimpose Klimt’s “The Kiss” on a crumbling residential block, Matisse’s circle dancers against a rubble-strewn street, and Gaugin’s Tahitian women on a refugee camp.

A section on arts produced in exile examines refugee theatre created in the youth centres of camps and urban slums. Via Skype, a cross-border Shakespeare production played by Syrian children cast Romeo in Jordan and Juliette in Homs. The performance was completed despite bombs, snipers and frequent communication cuts. The play’s conclusion was optimistically adapted. The doomed lovers threw away their poison and declared, “Enough blood! Why are you killing us? We want to live like the rest of the world!”

Through ‘applied theatre’ techniques women performed Euripides’ “Trojan Women” and so found a way to talk about the regime’s mass rape campaign. Director Yasmin Fedda incorporated the rehearsals into her prize-winning documentary “Queens of Syria”.

Of course, “Dancing in Damascus” doesn’t tell the whole story. There’s nothing on hip hop or several other important genres. The book tends to concentrate on ‘high art’ rather than the arguably more significant bottom-up production. Yet, with admirable concision and fluency, it assists what journalist Ammar al-Mamoun calls “an alternative revolutionary narrative to contest the media stories of Syrian refugees and victims”. It shows how, despite everything thrown at it, the revolution has democratised moral authority, turning artist-activists into the Arab world’s new “organic intellectuals”. As such it is an indispensable corrective to accounts which erase the Syrian people’s agency in favour of grand and often inaccurate geo-political representations. Beyond Syrian specifics, it is a testament to the essential role of culture anywhere in times of crisis.

Since I’ve started the Let’s Talk About Genocide series, over four years ago, the discussion around Israel in the context of the crime of genocide has grown substantially. And while many scholars, journalists, and human rights defenders have embarked on the arduous task of examining

Since I’ve started the Let’s Talk About Genocide series, over four years ago, the discussion around Israel in the context of the crime of genocide has grown substantially. And while many scholars, journalists, and human rights defenders have embarked on the arduous task of examining

Wednesday, April 5 at 6:00 PM

Wednesday, April 5 at 6:00 PM

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being,

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being,