These are extracts from Hasan Almossa’s as-yet unpublished book “I Was Born Twice”. Hasan is the founder of Kids Paradise, an NGO supporting vulnerable people and implementing sustainable projects in Syria.

These are extracts from Hasan Almossa’s as-yet unpublished book “I Was Born Twice”. Hasan is the founder of Kids Paradise, an NGO supporting vulnerable people and implementing sustainable projects in Syria.

My notebook

Dear reader

More than once, you will read the phrase, “I wrote in my notebook.” So what is this

notebook?

Unlike human beings, who usually have only one name, the notebook goes by many. However, there is a common thread between this notebook and human beings. Both go through different phases.

In each phase, the notebook was gradually shaped, growing like a plant until I managed to transfer it into this book so that it wouldn’t be lost, as had happened several times before. But now the notebook’s spirit has been captured in the book, forging a telepathic link with my memory that tried to save everything while only a little remained.

As narrow as a palm, and as small as a child, my notebook began its journey in life: I

used to put it in my pocket so I could jot down what people asked me. I also wrote down names and addresses of patients and the injured, so I could follow up with them.

As I wrote more and more, so my notebook grew. I wrote about war, common sayings and poems, and it also featured some stories. I wrote about pain as it was lived by ordinary people. I did not aim at publishing while I was writing, but rather I wrote to remember people’s pain, to follow up on their stories, and to solve their problems. Later, I started gathering the sorts of details that most media outlets cannot focus on. And yet these are important details.

Even though I was recording such details so as never to lose them, my notebook was lost more than once, such that I could not get it back. In 2015, I lost it for good, so I tried to collect the fragments of information still in my memory, as well as some things I’d written on small sheets of paper. With every name I wrote, I tried to restore my notebook. But many questions would pop into my thoughts without answers.

What happened to the one who’d dreamed of going to Europe? Did he ever arrive, or was he trapped in a prison on his way, or did he disappear inside the big whale’s belly of the ocean?

What happened to that woman who came with her injured son? Is he still alive, or has he died and left his mother wandering through a cruel life?

What happened to the old man who was asking for a prosthetic leg? Did he ever get it, or does he still live with a cane?

What about the girl whose father promised her a new eye while she was riding in the ambulance? Did she ever get a new eye, or was her father only trying to soothe her pain?

What about that family who sold all of their property to travel to Europe? Did the human trafficker keep his promise and help them to reach Germany?

The act of reorganizing the information in my notebook brought up thousands of

questions and put me in front of hundreds of unforgettable stories. Many of these stories were too painful to document, and I was afraid, too, that my bag would become as heavy as mountains. There are too many graves in exile: solitary graves, group graves, and lost graves. It was hard for me to put the destruction of past, present, and future in my bag and sleep beside it. I needed to sleep so I could continue my work, yet how could I sleep alongside all these tragedies?

And so I was sleepless beside these human tragedies. I often wished a bullet had ended my life so that I didn’t have to witness these stories I carry.

The buzz of the bullet stays with me: for three months, its buzz kept visiting me from

time to time. I wished to sleep or, as we call it, go to a minor death, in order to comfort my tired soul. Others wished to relax forever and turn to the real Death.

In these pages, I wrote what I felt, what my pen could write, and what I felt obliged to record.

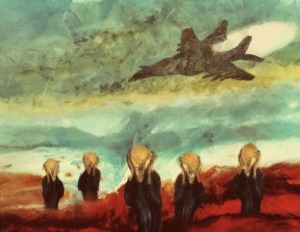

In 2011, people in the eastern Ghouta (and throughout Syria) protested for freedom, dignity and social justice. The Assad regime replied with gunfire, mass arrests, torture and rape. The people formed self-defence militias in response. Then the regime escalated harder, deploying artillery and warplanes against densely-packed neighbourhoods. In August 2013 it choked over a thousand people to death with sarin gas. Since then the area has been besieged so tightly that infants and the elderly die of malnutrition.

In 2011, people in the eastern Ghouta (and throughout Syria) protested for freedom, dignity and social justice. The Assad regime replied with gunfire, mass arrests, torture and rape. The people formed self-defence militias in response. Then the regime escalated harder, deploying artillery and warplanes against densely-packed neighbourhoods. In August 2013 it choked over a thousand people to death with sarin gas. Since then the area has been besieged so tightly that infants and the elderly die of malnutrition.

Baghdad, 2005. Occupied Iraq is hurtling into civil war. Gunmen clutch rifles “like farmers with spades” and cars explode seemingly at random. Realism may not be able to do justice to such horror, but this darkly delightful novel by Ahmed Saadawi – by combining humour and a traumatised version of magical realism – certainly begins to.

Baghdad, 2005. Occupied Iraq is hurtling into civil war. Gunmen clutch rifles “like farmers with spades” and cars explode seemingly at random. Realism may not be able to do justice to such horror, but this darkly delightful novel by Ahmed Saadawi – by combining humour and a traumatised version of magical realism – certainly begins to.

The Rohingya Muslims are currently the world’s most persecuted minority. Since last year at least 625,000, over half the total population, have fled slaughter in Myanmar (also known as Burma). This is only the latest wave in a series of killings and expulsions starting in 1978. The UN calls it a ‘textbook example’ of ethnic cleansing.

The Rohingya Muslims are currently the world’s most persecuted minority. Since last year at least 625,000, over half the total population, have fled slaughter in Myanmar (also known as Burma). This is only the latest wave in a series of killings and expulsions starting in 1978. The UN calls it a ‘textbook example’ of ethnic cleansing. I’m very happy to say that “Burning Country” has been

I’m very happy to say that “Burning Country” has been

This was first published

This was first published  I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being,

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being,