A special programme looking at Egypt under Hosni Mubarak.

Category: Economy

Going after the military budget

The great Ralph Nader: “Ron Paul & Bernie Sanders Have Teamed Up To Go After The Military Budget”

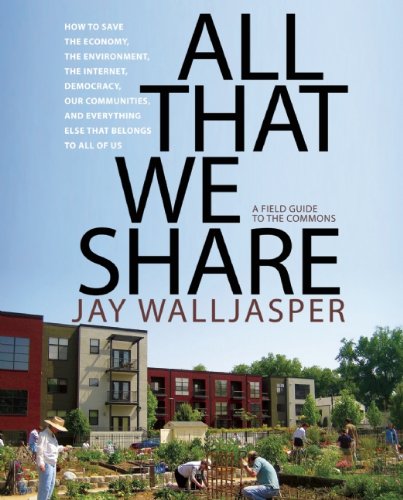

“All That We Share” isn’t enough

by Robert Jensen

A review of All That We Share: A Field Guide to the Commons/How to Save the Economy, the Environment, the Internet, Democracy, Our Communities, and Everything Else That Belongs to All of Us by Jay Walljasper and On the Commons

The New Press, 2010, 288 pages, $18.95

All That We Share is an exciting and exasperating book. The excitement comes from the many voices arguing to place “the commons” at the center of planning for a viable future. The exasperation comes from the volume’s failure to critique the political and economic systems that we must transcend if there is to be a future for the commons.

All That We Share is an exciting and exasperating book. The excitement comes from the many voices arguing to place “the commons” at the center of planning for a viable future. The exasperation comes from the volume’s failure to critique the political and economic systems that we must transcend if there is to be a future for the commons.

In the preface, the book’s editor and primary writer, Jay Walljasper, describes how he came to understand the commons as a “unifying theme” that helped him see the world differently and led him to believe that “as more people become aware of it, the commons will spark countless initiatives that make a difference for the future of our communities and the planet.”

Defining the commons as “what we share” physically and culturally — from the air and water to the internet and open-source software — the contributors recognize that a society that defines success by individuals’ accumulation of stuff will erode our humanity and destroy the planet’s ecosystems. Walljasper calls for a “complete retooling” and “a paradigm shift that revises the core principles that guide our culture top to bottom.” No argument there. Unfortunately the book avoids addressing the specific paradigms we must confront. Is commons-based transformation possible within a capitalist economy based on predatory principles and an industrial production model built on easy access to cheap concentrated energy?

Thousands Protest Irish Nightmare Economy

TheRealNews — Leo Panitch on how the US created financial crisis and European banks have turned the Irish Miracle into a nightmare.

Economics: doing business as if people mattered

by Robert Jensen

This article is Part 1 of a 3 part collection of essays by University of Texas at Austin Professor Robert Jensen on important issues that should be highlighted during this year’s US mid-term election campaigns.

When politicians talk economics these days, they argue a lot about the budget deficit. That’s crucial to our economic future, but in the contemporary workplace there’s an equally threatening problem — the democracy deficit.

In an economy dominated by corporations, most people spend their work lives in hierarchical settings in which they have no chance to participate in the decisions that most affect their lives. The typical business structure is, in fact, authoritarian — owners and managers give orders, and workers follow them. Those in charge would like us to believe that’s the only way to organize an economy, but the cooperative movement has a different vision.

Cooperative businesses that are owned and operated by workers offer an exciting alternative to the top-down organization of most businesses. In a time of crisis, when we desperately need new ways of thinking about how to organize our economic activity, cooperatives deserve more attention.

First, the many successful cooperatives remind us that we ordinary people are quite capable of running our own lives. While we endorse democracy in the political arena, many assume it’s impossible at work. Cooperatives prove that wrong, not only by producing goods and services but by enriching the lives of the workers through a commitment to shared decision-making and responsibility.

Continue reading “Economics: doing business as if people mattered”

Naomi Klein, Hernando de Soto and Joseph Stiglitz on Economic Power

Naomi Klein, Hernando de Soto and Joseph Stiglitz speaking on economic power at the Graduate Centre, CUNY, moderated by David Harvey. See speaker biographies over the fold. From the fora.tv series ‘Is capitalism dead‘? Run time is 62 minutes, with a ten minute preview.

Vodpod videos no longer available.Continue reading “Naomi Klein, Hernando de Soto and Joseph Stiglitz on Economic Power”

The Spirit Level

I haven’t read The Spirit Level yet, but in his last book Ill Fares the Land, the late Tony Judt quotes from it extensively. The authors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett base their work on what they call ‘evidence-based politics,’ an approach I also favour (as opposed to the theology that generally passes for analysis on the left). That the book has had an impact is confirmed by the fact that recently a host of conservative and neoconservative think-tanks (led by the raving-mad Policy Exchange) have launched a concerted campaign against it. Here is an interview with the authors in which they explain the argument of the book followed by Robert Booth’s report in the Guardian about the right-wing assault on their work.

Bestseller with cross-party support arguing that equality is better for all comes under attack from thinktanks

It was an idea that seemed to unite the political classes. Everyone from David Cameron to Labour leadership candidates Ed and David Miliband have embraced a book by a pair of low-profile North Yorkshire social scientists called The Spirit Level.

Their 274-page book, a mix of “eureka!” insights and statistical analysis, makes the arresting claim that income inequality is the root of pretty much every social ill – murder, obesity, teenage pregnancy, depression. Inequality even limits life expectancy itself, they said.

The killer line for politicians seeking to attract swing voters was that greater equality is not just better for the poor but for the middle classes and the rich too.

Keynes is Back

I am reading Soldiers of Reason, Alex Abellas hagiographic account of the rise of the RAND Corporation in which he shows how ideas that originated with its mathematicians have by virtue of its proximity to power come to dominate such diverse disciplines as political science, international relations, philosophy, sociology, (even religious studies!) and economics (NB: for more on the subject, don’t miss Adam Curtis’s classic film The Trap). Prominent among them are systems analysis, game theory, and rational choice theory. The latter gave us everything from the arms race to the recent financial collapse. In his review of Robert Skidelsky’s Keynes: The Return of the Master, the new biography of John Maynard Keynes, Joseph Stiglitz writes:

We should be clear about this: economic theory never provided much support for these free-market views. Theories of imperfect and asymmetric information in markets had undermined every one of the ‘efficient market’ doctrines, even before they became fashionable in the Reagan-Thatcher era. Bruce Greenwald and I had explained that Adam Smith’s hand was not in fact invisible: it wasn’t there. Sanford Grossman and I had explained that if markets were as efficient in transmitting information as the free marketeers claimed, no one would have any incentive to gather and process it. Free marketeers, and the special interests that benefited from their doctrines, paid little attention to these inconvenient truths.

While economists who criticised the ruling free-market paradigm often still employed, as a matter of convenience, simple models of ‘rational’ expectations (that is, they assumed that individuals ‘rationally’ used all the information that they had available), they departed from the ruling paradigm in assuming that different individuals had access to different information. Their aim was to show that the standard paradigm was no longer valid when there was even this seemingly small and obviously reasonable change in assumptions. They showed, for instance, that unfettered markets were not efficient, and could be characterised by persistent unemployment. But if the economy behaves so poorly when such small realistic changes are made to the paradigm, what could we expect if we added further elements of realism, such as bouts of irrational optimism and pessimism, the ‘panics and manias’ that break out repeatedly in markets all over the world?

Joseph Stiglitz on Media Matters with Bob McChesney

Joseph Stiglitz on BookTV, interviewed by Lori Wallach of Public Citizen.

On the abuse of language

Tony Judt on linguistic subterfuges practised in Europe and America.

In America the misuse of language is usually cultural rather than political. People will accuse Obama of being a socialist. Italians would say magari – if only. However, no one takes this very seriously. What we have instead in the US is cultural communities policing what can and can’t be said, and that shapes how we define difference. The idea is that you can’t have an elite, since elitism is undemocratic and unegalitarian. Therefore, you always make the point that people are in some important way the same. If they are badly disabled like me, they are ‘differently abled’, which I find very amusing. It is not a ‘different’ ability: it is no ability. But since it’s politically uncomfortable to distinguish between people who can do things and people who can’t, the latter are described as separate but equal. There are numerous things wrong with this: first, it is lousy language; second, it creates the illusion of sameness or achievement in its absence; third, it conceals the effects of real power and capacity, real wealth and influence. You describe everyone as having the same chances when actually some people have more chances than others. And with this cheating language of equality deep inequality is allowed to happen much more easily.

USA and USSR: Accidental Parallels?

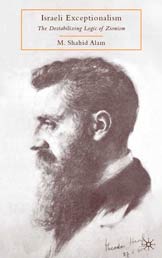

M. Shahid Alam

Is the question of parallels between the USA and the USSR idle, even mischievous? Perhaps, it is neither, but, on the contrary, deserves our serious consideration.

Is the question of parallels between the USA and the USSR idle, even mischievous? Perhaps, it is neither, but, on the contrary, deserves our serious consideration.

During the Cold War, the USA and USSR were arch rivals, each the antipodes of the other. For some four decades, they battled each other for ‘survival’ and global hegemony, staring down at each other with nuclear tipped missiles, ready at the push of a button to consummate mutually assured destruction. What parallels could there possibly exist between such irreconcilable antagonists?

Dismissively, the skeptic might retort that their similarities start and end with the first two letters in their names. The USA won and the USSR lost the Cold War. With all four of the letters in its name, the USSR is dead and gone. Its successor state, Russia, now ranks a distant second behind the USA in military power, a position it retains only by virtue of its nuclear arsenal. Measured in international dollars, the Russian economy ranked eighth in the world in 2009, trailing behind its former client, India.

On the other hand, the USA still believes it can ride roughshod over much of the world like a Colossus. It came close to doing this for a few years after the collapse of communism. In the years since its occupation of Iraq, that image has been deflated quite a bit. Haven’t the events of the last decade – the growing challenge to its hegemony in Latin America, the economic rise of India and China, and the recovery of Russia from its collapse of the previous decade – downsized the Colossus of the 1990s? Indeed, the near collapse of its economy in 2008 appears to have brought the Colossus down on its knees.