How leftists were blinded to Trump’s winning prospects

The gamble was this, and many on the left were sure the odds were stacked: Hillary Clinton would overcome the sweeping forces of global reaction and be the next president of the United States, liberating the politically savvy to focus on her–the locus of real power, the fascist, but with a smile and a pantsuit–and come out looking prescient as all hell for having never bought into liberal hysteria over Donald J. Trump. Say what you will about Trump, this woke-as-fuck cadre claimed, at least he wouldn’t nuke Moscow over the proxy war in Syria.

Gambling that Clinton was the one and Trump just a boogeyman distraction did, at some point, seem reasonably safe, and so we were confidently assured. “It’s obvious she’ll win,” Salon’s Benjamin Norton observed in a late June microblog. “Wall Street, most media, State Dept., foreign policy elites, neocons, etc. all back Clinton.” Striking a similar tone, Zaid Jilani of the Intercept dismissed the possibility of a proto-fascist billionaire’s ascendance to the White House as “theatrics.”

“Trump has no policies, no real team, no real campaign,” Jilani argued. “He’s about as dangerous as a fruit fly.”

The ballots having been cast, we can confidently state: Shit.

The left isn’t alone in having gotten this wrong, but what might be cause for introspection is why the political subculture that prides itself on its superior analysis of reality didn’t grasp what was happening. It’s not that criticizing the neoliberal hawk in the race was not the right thing to do, but that the dogma that she was a shoo-in led some to lay off the man who was to become president.

Glenn Greenwald spent the weeks leading up to the election portraying the far-right demagogue who was set to become the world’s most powerful man as a victim of mainstream media bias and center-left anti-communism. At the same time, he compared the media’s inquiries into Trump’s Russian oligarch ties to Senator Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee (which Trump surrogate Newt Gingrich actually wishes to revive).

Trump, Greenwald told Slate, adheres to a “coherent philosophy that is non-interventionist.” This, at the time, was offered as part of the explanation for why the liberal establishment was going so hard on Trump over his alleged ties to Russia. Greenwald stuck to this line even after Trump called for many more airstrikes around the globe and “bombing the hell out of” Libya, Iraq and Syria in particular. As with other contemporary leftist apologism for a fascist, this one began with a liberal. (“Donald the Dove, Hillary the Hawk,” was the title of Maureen Dowd’s column in the New York Times.)

The Green Party’s Jill Stein took it further, saying America’s Berlusconi would keep us out of World War III. “Hillary Clinton’s foreign policy is much scarier than Donald Trump’s,” she tweeted alongside the hashtag #PeaceOffensive, contrasting the fascist with the neoliberal by saying that at least the former “does not want to go to war with Russia.” By the end of the campaign, it was commonplace to see Trump–say what you will–referred to as a practitioner of “know-nothing isolationism,” as journalist Rania Khalek did, contrasting that ideology with his opponent’s bombs-away neo-conservatism.

We have a few weeks to go before Trump gains the power to drone strike weddings abroad, a modern presidential rite of passage that, judging by the rise in global defense stocks since his election, investors are convinced he will continue as the next Commander-in-Chief. His desire for peace with Russia, the smart money says, won’t mean peace elsewhere, like Syria, where he has proposed an escalated bombing campaign in alliance with Vladimir Putin and Bashar al-Assad.

Without any Trump-embossed missiles having yet been fired, it already seems like a singularly dumb, quaint, and naive idea that he would drop less of them than Hillary. Why, then, did some on the left suggest the guy on the right would be a man of relative peace?

Because it wasn’t about him, and he wasn’t supposed to win.

“I’d assumed that the danger of Trump and the danger of Clinton were of two different orders,” explained British leftist Sam Kriss in a post-mortem. Trump was a danger because of what he said, but “Clinton was dangerous because of what she would actually do, because Clinton was going to win the election. I was a sucker, the kind who gets duped precisely by believing himself to be too smart for any kind of con.”

The problem wasn’t that it was wrong to believe Clinton a danger, but that dwelling on the evils of the horrible, neoliberal status quo she represented blinded some to the fact that things could get worse. In some cases, this led to a failure to effectively critique and prepare for the next President, from the left.

Trump won, Kriss argues, “because the standard formula of American liberalism–eternal war abroad coupled with rationally administered dispossession at home and an ethics centered on where people should be allowed to piss and shit–is a toxic and unlovable ideology.” As rhetoric, it pleases those who adhere to the leftist consensus: Yes, racism is a real problem and social justice matters, but neither is as important as the class war. Scratching away the smarm, though, yields no better understanding of U.S. politics.

No candidate was running on a platform of peace: Clinton had a record of supporting war while Trump was running on the promise of doing war more brutally and efficiently, stripped of limp-wristed anchors like democracy promotion and nation-building. People who voted on either the Republican or Democratic ticket were not casting their ballots against empire. Nor were they voting against an ethics “centered” on where people relieve themselves, by which Kriss means the revanchist crackdown over transgender Americans using bathrooms that match their gender identity.

Not only is the implication that Trump votes were a response to “politically correct” defenses of basic human rights morally wrong, but it’s also at odds with the complementary claim that they voted for jobs. Neither claim is backed by what happened on Election Day. In North Carolina, both the Republican governor and Republican lawmaker who prided themselves on a law banning transgender people from using public bathrooms lost to Democrats whose opposition to the transphobic law was a centerpiece of their campaigns.

Kriss and others nodding at the “piss and shit” shorthand for “identity politics” do not, presumably, oppose people using bathrooms that match their gender, much less believe a group of oppressed people, nearly half of whom have attempted suicide, deserve to be discriminated against and assaulted for that choice.

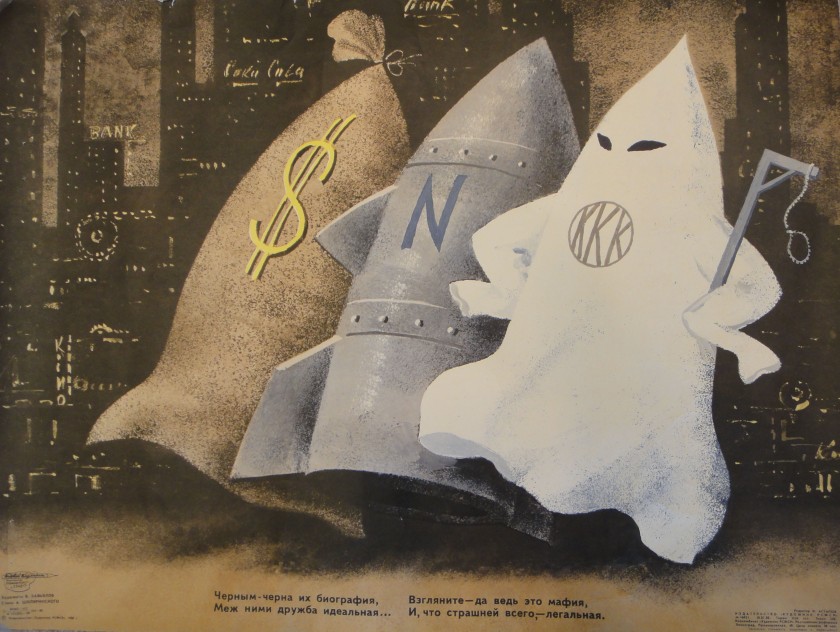

But what this leftist cadre dismissive of Trump’s prospects represents, above all, is an antiquated ethics that centers and romanticizes a proletariat class that doesn’t really exist in the U.S. In this ethics, issues pertaining specifically to the rights of racial minorities or the LGBT community are seen as neoliberal deflections from what really matters. As Jacobin editor Connor Kilpatrick argues, claims of prejudice among the white rural electorate are an elite tactic to deflect from elite failures. “Diversity rhetoric,” he maintains, “has obscured that 63 percent of [the] USA is white,” while “only 3.8 percent LGBT.” By this math, it’s just political correctness that has been alienating all those budding socialists who wear t-shirts emblazoned with the Confederate flag.

It’s not that Trump voters lacked material concerns. The neoliberal consensus has failed, pushing millions of Americans into precarious lines of work. This is part of the reason why Trump did better with members of unions than Mitt Romney did in 2012. But their class politics shouldn’t be overstated either: Trump only did four percent better than the last Republican presidential nominee, losing union workers by 19 points to Clinton, according to the AFL-CIO. Likewise, Trump did better with those making under $50,000 by about 3 percent compared to Romney. Most working-class voters sided with Clinton over Trump, who won thanks to 290 electors, but which is expected to be 2 million votes less. Others looked at them both, felt nauseous, and decided to stay home.

U.S. liberalism is a toxic ideology, at home and abroad, but jettisoning “identity politics”–the defense of vulnerable people on issues that are matters of life and death–is the absolute wrong lesson to take from a four percent swing among registered voters who actually decided to vote. Trump’s campaign was itself based on identity: whiteness. The response is not abandoning identity in politics, but developing a more radical version of it that advocates equality within a socialist critique of an economic system designed by and for predominantly white men with capital.

What the left needs, is to be defined by more than just its necessary anti-liberalism, wherein explanations for right-wing revanchism that rely on racism are written off as neoliberal excuse-making. Sure, Trump’s voters may not be 60 million Klansmen, but we shouldn’t whitewash the fact that millions had no problem expressing their discontent with a vote for a racist misogynist whose campaign events looked like Klan rallies. The latter were okay with expressing whiteness–and the whiteness of the final vote tally was overwhelming–at the cost of everyone who didn’t look like them.

Clinton’s Death Star liberalism was the most progressive policy platform yet in a general election, thanks in no small part to the push from Sanders. But that’s not saying much, and ultimately, anything she promised was already tainted by her embodiment, to right and left voters, of everything that’s wrong with the status quo. But it would be a ghastly mistake to take from her loss the lesson that the left ought to ignore the human rights of the most vulnerable in order to make short-term gains with a racist white minority.

As leftists, our ethics must be centered not on the four percent, but on the growing, soon-to-be majority of people excluded from the Trump voter coalition–those who were under assault from white supremacy and “traditional” bigoted values long before November 8 and will only continue to be assaulted under his regime. A lot should be thrown out in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s loss, beginning with the candidate herself, but detoxing this country of liberalism should mean replacing her brand of center-left corporatism with an economic program of radical wealth redistribution based on anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-homophobic, and anti-transphobic values. We don’t need to wait until after the class war to do things as basic as naming white supremacy or letting people use the bathroom that best corresponds to their gender identity.

Charles Davis is a journalist whose work has been published by outlets such as Al Jazeera, The Nation and The New Republic. Follow him on Twitter: @charliearchy

In 2011, people in the eastern Ghouta (and throughout Syria) protested for freedom, dignity and social justice. The Assad regime replied with gunfire, mass arrests, torture and rape. The people formed self-defence militias in response. Then the regime escalated harder, deploying artillery and warplanes against densely-packed neighbourhoods. In August 2013 it choked over a thousand people to death with sarin gas. Since then the area has been besieged so tightly that infants and the elderly die of malnutrition.

In 2011, people in the eastern Ghouta (and throughout Syria) protested for freedom, dignity and social justice. The Assad regime replied with gunfire, mass arrests, torture and rape. The people formed self-defence militias in response. Then the regime escalated harder, deploying artillery and warplanes against densely-packed neighbourhoods. In August 2013 it choked over a thousand people to death with sarin gas. Since then the area has been besieged so tightly that infants and the elderly die of malnutrition.