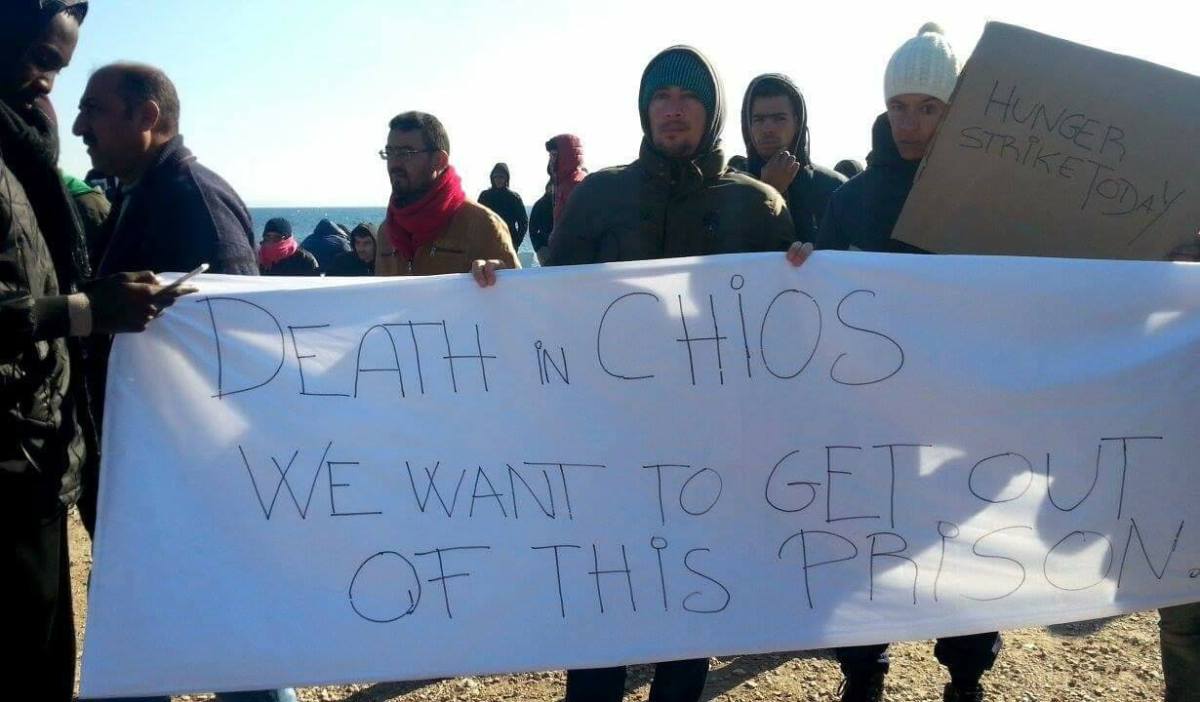

Editor’s note: An edited version of this was published by the Times Literary Supplement. (Photo: Anna Pantelia)

By Muhammad Idrees Ahmad

The only surviving example of William Shakespeare’s handwriting is preserved at the British Library in the manuscript of the play The Book of Sir Thomas More. Shakespeare’s contribution to the co-authored play is a speech by deputy sheriff Thomas More addressed to a mob rioting against immigrants. He appeals to the mob’s empathy by inviting them to imagine themselves in the shoes of the “strangers”, exiled from home.

What country, by the nature of your error,

Should give you harbour? Go you to France or Flanders,

To any German province, Spain or Portugal,

Nay, anywhere that not adheres to England,

Why, you must needs be strangers, would you be pleas’d

To find a nation of such barbarous temper

That breaking out in hideous violence

Would not afford you an abode on earth.

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, not that the elements

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But charter’d unto them? What would you think

To be us’d thus? This is the strangers’ case

And this your mountainish inhumanity.

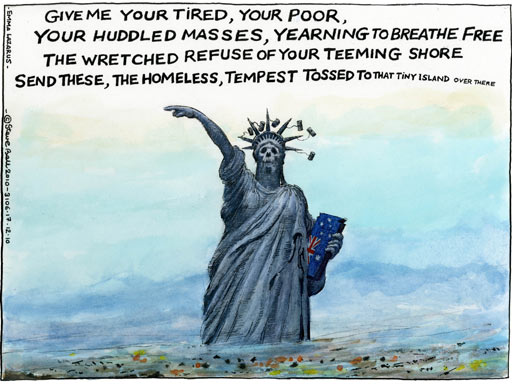

Over four centuries later, empathy for the stranger remains an uncertain virtue. Since 2015, when the media elevated refugees to the status of a “crisis”, their influx has sharply declined (from a peak of over 221,000 in 2015 to less than 11,000 in 2018). However this reduction has yet to be acknowledged in the fevered registers of Europe’s political discourse. Immigration—or, rather, its perception—is roiling an entire continent, empowering the right and seducing even left-wing populists into xenophobia. The consequences have been catastrophic, in political, economic, and human terms.

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being,

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being,