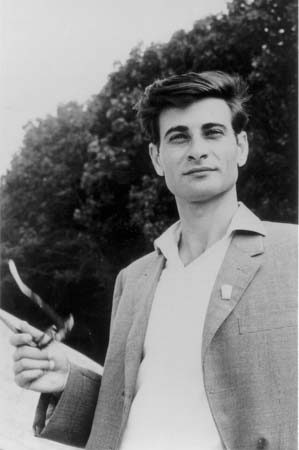

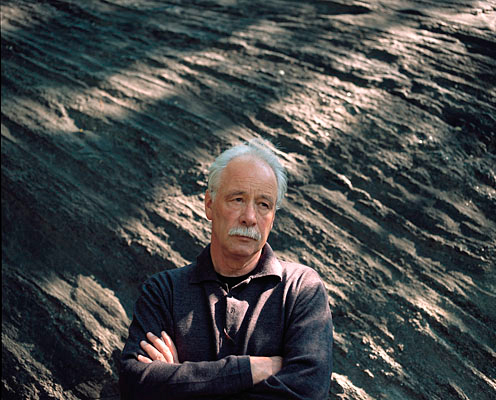

Essayist, lawyer, and PULSE contributor Chase Madar’s much-awaited book The Passion of Bradley Manning: The Story of the Suspect behind the Largest Security Breach in U.S. History is out this month from O/R Books.

Essayist, lawyer, and PULSE contributor Chase Madar’s much-awaited book The Passion of Bradley Manning: The Story of the Suspect behind the Largest Security Breach in U.S. History is out this month from O/R Books.

The following is an excerpt from Kelly B. Vlahos’ recent review of the book at Antiwar.com:

It might be too easy to invoke Manning as martyr two days after Palm Sunday, when Christians observe the betrayal, humiliation and crucifixion of Jesus Christ two thousand years ago. While it is not our intention to compare Manning to the Christian Son of God, who according to Gospel, rose from the dead, humanity’s sins forgiven, on Easter Sunday, author Chase Madar lays out a deft argument that Manning has indeed sacrificed everything for his country’s sins in his aptly entitled new book, The Passion of Bradley Manning.

“I wanted to write a full-out defense of his alleged deeds — a political and moral defense,” Madar told Antiwar.com in a recent interview. And he has. As Madar points out, there are “many people in history who have died and sacrificed for their cause.” The Passion makes an industrious case that Manning did what he did for a cause: to give the people the information they need and deserve about what their government is doing in their name. Transparency — Robin Hood style.

“What I find remarkable and praiseworthy is, he was not — despite having this terrible time getting bullied and messed with constantly — leaking these things to get revenge,” Madar said. “He was a true believer in patriotic duty and military service, I think. If you look at the chat logs, he was very clear about his motives for leaking, that this was what the public should know, so that we as a country could make better decisions.”