Getting one’s picture taken with the Dalai Lama or the Pope will guarantee neither Buddhist enlightenment nor beatification: my apologies for shattering the hopes of some New Agers. Similarly, entering the Ka’aba in Burtonesque disguise — specially minus his arguably relevant though shifty linguistic skills and textual knowledge — will not and cannot necessarily guarantee much “learning” about Islam.

by Huma Dar

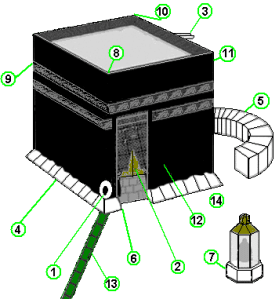

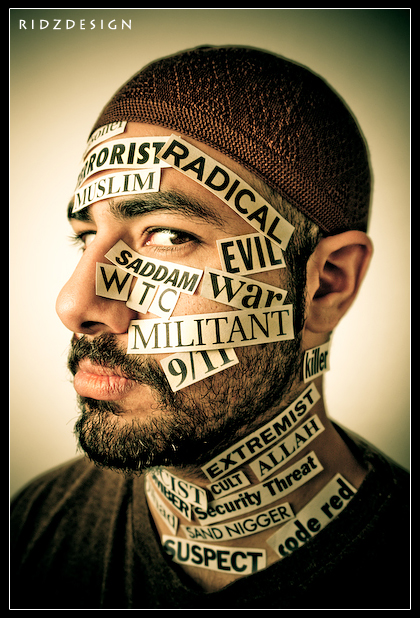

The March 10, 2010, page A27 of the New York edition of New York Times carries an Op-Ed piece by Maureen Dowd titled, “Pilgrim Non Grata in Mecca.” Dowd writes about her desire to “learn about the religion that smashed into the American consciousness on 9/11” via “sneaking” into Mecca in “a black masquerade cloak.” Her self-proclaimed inspiration is Richard Burton’s “illicit pilgrim[age] to the sacred black granite cube…in Arab garb” thereby “infiltrat[ing] the holiest place in Islam, the Kaaba [sic].”

Dowd, however, decides to “learn about Islam” in a way “less sneaky,” “disrespectful,” or “dangerous” and yet more entitled and privileged than Richard Burton could ever have dreamed of. She herself describes Burton as “the 19th-century British adventurer, translator of “The Arabian Nights” and the “Kama Sutra” and self-described ‘amateur barbarian.'” The words “illicit,” “Kama Sutra,” and “infiltration” and Dowd’s voyeuristic desires resonate with the Orientalism of yore. Moreover Dowd’s valuable US passport and USA’s special relationship with Saudi Arabia (read: enabling of the oppressive monarchy) entitle her to meet Prince Saud al-Faisal, the Saudi foreign minister — of the “sometimes sly demeanor” — on her “odyssey” to that country. “Infiltration” in disguise is no longer required, and yet this ease of access also disguises and makes more difficult the complexity of any real learning.

Dowd “presses” al-Faisal for the privilege to watch in Mecca, the “deeply private rituals” and “gawk at the parade of religious costumes fashioned from loose white sheets” although she knows in advance that “Saudis understandably have zero interest in outraging the rest of the Muslim world.” While talking to this high-ranking minister, Dowd bristles at al-Faisal’s reassuring suggestion that if she desired to see any mosque in a place other than in Mecca or Medina, and was prevented from doing so, all she had to do was to contact the “emir of the region” who would comply and enable the fulfillment of her desires. (Anyone else reminded of Aladdin’s djinn/genie?) Without conceding the irony of the situation that she, after all, is speaking to Prince al-Faisal, the Saudi foreign minister, Dowd quips, “Sure. Just call the emir. I bet he’s listed.” Imagine what Richard Burton would have done with the special privileges of this particular magic lamp provided by the New World Order!

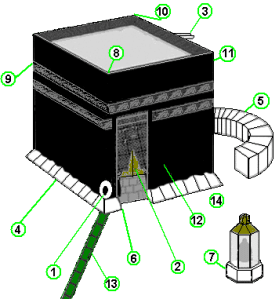

Finally Dowd does indeed witness the Hajj — in an IMAX theatre watching Journey to Mecca: In the Footsteps of Ibn Battuta. Dowd, much to her surprise, makes the belated discovery that “the Kaaba [sic] was built by “Abraham, the father of the Jews” [why Jews only?]— a reminder that the faiths have a lot to learn from each other.” It is also a reminder that journalists like Ms. Maureen Dowd have a lot of homework to do before they set out on their surely expensive travels — and I am not even including the much recommended language lessons. Any commonly available text on Islam, for example by Karen Armstrong, Jamal Elias, Michael Sells, or Ziauddin Sardar, might have served the purpose. Dowd could thus have avoided relying solely on the “amateur barbarian” Richard Burton or Newsweek’s own Fareed Zakaria. The former’s scholarly credentials are hardly beyond doubt — see his problematic remarks on “Jewish human sacrifice” in The Jew, the Gipsy and el Islam (1898). The latter’s forte is not his knowledge of Islam — or at least no more than Zakaria’s mentor, Samuel Huntington’s forte is Christianity. Dowd might thus have disabused herself of the notion of “the sacred black granite cube.” The “sacred black” stone is not a “cube” and neither is the “sacred cube” — the Ka’aba — all granite!

Getting one’s picture taken with the Dalai Lama or the Pope will guarantee neither Buddhist enlightenment nor beatification: my apologies for shattering the hopes of some New Agers. Similarly, entering the Ka’aba in Burtonesque disguise — specially minus his arguably relevant though shifty linguistic skills and textual knowledge (See Parama Roy’s excellent essay for more on Burton) — will not and cannot necessarily guarantee much “learning” about Islam. On the other hand, a trip to any local library with a willingness to read and learn, and engagement with an open mind in meaningful conversations with the (gasp!) American Muslims, might be better starting points for undertaking this particular journey.

Did the Editor of The New York Times not know the price difference between the ticket to the IMAX theatre plus membership to a local library and the cost of Dowd’s lavish travels to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia? The Neo-Orientalist fantasy to tread in the footsteps of Sir Richard Burton is accelerated with privilege and precisely because of this privilege skips and misses its target even more widely.

It is in the spirit of a gift that I offer Ms. Dowd this image:

|

Labeled elements are as follows: 1 – The Black Stone; 2 – Door of the Kaaba; 3. Gutter to remove rainwater; 4 – Base of the Kaaba; 5 – Al-Hatim; 6 – Al-Multazam (the wall between the door of the Kaaba and black stone); 7 – The Station of Ibrahim; 8 – Angle of the Black Stone; 9 – Angle of Yemen; 10 – Angle of Syria; 11 – Angle of Iraq; 12 – Kiswa (veil covering the Kaaba); 13 – Band of marble marking the beginning and end of rounds; 14 – The Station of Gabriel.

|

|

|