by Huma Dar

for my N, Z, many Shahids, and the One

The moon did not become the sun.

It just fell on the desert

in great sheets, reams

of silver handmade by you.

The night is your cottage industry now,

the day is your brisk emporium.

The world is full of paper.

Write to me.

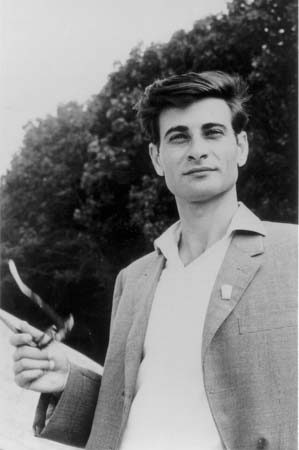

—Agha Shahid Ali, “Stationery”

(I)

The tilted goblet drips

mocking

Pacific amber:

liquid lunatic luminous.

And makes a slippery mess

of Highway 1

the night

memory and desire —

relentless, ebon, a plumbless

dream of falling.

Like tresses distraught

entwining your imagined arm

(make the bleeding black night

all yours)

your aching memories knotted in my gut

my exiled ghost lost, found

and willfully entangled

again

in the lines of your words

your stone-cold feet in my shaalfa —

an ablution performed in blood.