by Huma Dar

[read Part I Part II Part III]

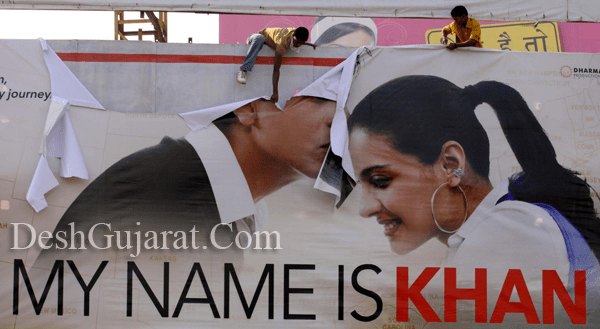

In the second half of the film, My Name is Khan (2010), Karan Johar shows that Rizwan Khan’s wife, Mandira (played by Kajol) is on a personal journey to obtain justice for her son and accountability from the perpetrators of a hate crime. It is thus ironic that Mandira’s own negligence towards Rizwan Khan (played by SRK) and the lack of accountability for making him set off on an ostensibly unfeasible mission, albeit in a fit of grief and anger, is not problematized at all in the film. A mission that might very well have remained unfulfilled but for Rizwan Khan’s Herculean efforts, his unusual talents and disabilities, and a string of exceptional circumstances. Rizwan Khan, given his Asperger’s syndrome, “fear of new places,” and his Muslimness (actively practiced), would have been equally, if not more, susceptible to the kind of hate crime that victimized Mandira’s son. After the initial outburst at the place of death, Mandira had had enough time to re-think the consequences of her angry directive to Khan, yet she never apologizes to Khan. Here too, the immediate context of Bollywood, the multiple Hindu-Muslim marriages amongst the stars of Bombay, and the general lack of acceptance of such marriages in mainstream India are crucial to keep in mind.

Continue reading “A Suitable Boy, “Decent” People, and Names that Pass (The King is Out: Part IV)”

When is dissent hip? This is the subject of the following discussion hosted by the excellent

When is dissent hip? This is the subject of the following discussion hosted by the excellent  by Raymond Deane

by Raymond Deane

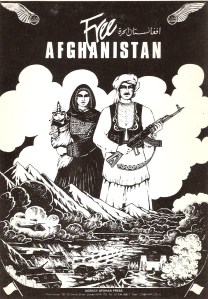

A British artist made these impressive propaganda posters during the Afghan war against the Soviet occupation. They were also printed as postcards. The picture to the right was sent out as a christmas card by Agency Afghan Press in the UK, prompting London’s Evening Standard to wonder, jokingly, if the three figures represented Joseph, Mary and Jesus. The picture to the left was made for Gulbedeen Hekmatyar’s Hizb-i-Islami, which then had a London office. The pictures raised no horrified eyebrows in the UK – of course not: the Afghan people and the Thatcher and Reagan administrations were all on the same side, for freedom, against godless Soviet communism interfering with a traditional culture. Today, however, Hekmatyar is fighting the NATO occupation of his country, and were a British artist to dare paint an Afghan mujahid, with Qur’an in one hand and kalashnikov in the other, standing on an American flag, underneath a calligraphed ‘Allahu Akbar’, he would quite probably be charged under anti-terror legislation.

A British artist made these impressive propaganda posters during the Afghan war against the Soviet occupation. They were also printed as postcards. The picture to the right was sent out as a christmas card by Agency Afghan Press in the UK, prompting London’s Evening Standard to wonder, jokingly, if the three figures represented Joseph, Mary and Jesus. The picture to the left was made for Gulbedeen Hekmatyar’s Hizb-i-Islami, which then had a London office. The pictures raised no horrified eyebrows in the UK – of course not: the Afghan people and the Thatcher and Reagan administrations were all on the same side, for freedom, against godless Soviet communism interfering with a traditional culture. Today, however, Hekmatyar is fighting the NATO occupation of his country, and were a British artist to dare paint an Afghan mujahid, with Qur’an in one hand and kalashnikov in the other, standing on an American flag, underneath a calligraphed ‘Allahu Akbar’, he would quite probably be charged under anti-terror legislation.