by Huma Dar

[Read Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V]

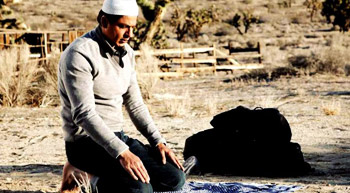

[I]n one scene I wanted to have just a half open door and I wanted to be shown saying namaz once. We couldn’t take that shot. Then we put that bit where I say the prayer: Nasrun minal lahe wah fatahun kareeb (God give me strength to win) [sic] [Victory is Allah’s, and the opening/victory is close] which is my own prayer too. I don’t think we should intellectualise entertainment. See the fun of it.

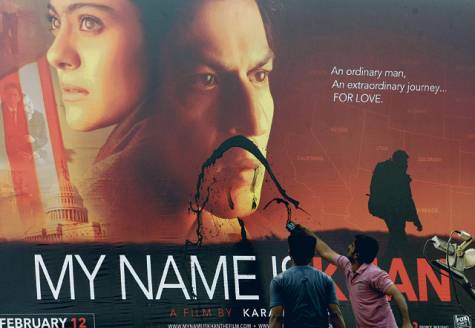

This is how Shahrukh Khan describes his experience working in the film Chak De! India (Dir: Shimit Amin, 2007). With apologies to King Khan for discarding his proposal to not “intellectualize” films, yet taking due “fun” in it, I argue that it is only in My Name is Khan (Dir: Karan Johar, 2010) that the King finally comes “out” as a Muslim. No “half open door” is needed. This coming out affords particular visceral pleasures to an audience (or at least a large section of it spread across the globe) long resigned to seeing SRK endlessly and persistently marked by the specifically filmic variety of Hinduness practiced in Bollywood: doing various pujas and aartis at different Hindu temples, or adorning his spouses’ hair-parting with sindhoor and smearing his own forehead with tilaks. This performative Hinduization of Shahrukh Khan in Urdu-Hindi cinema is unrelenting precisely due to the dogged presumption of SRK’s Muslimness that is not easily obscured. “In my films I have been going to temples and singing bhajans; no one has questioned that,” (my emphasis) SRK exclaims in the same interview. No one “questions” the diegetic (filmic) Hinduness of SRK; it is expected and mandatory. With the increasing and explicit polarization in India since 1990s, the anxiety around Muslimness is such that it requires perpetual masking: an iterative performance of Hinduness, secular or otherwise. When the mask slips off, the performance is momentarily paused – as when SRK plays a Muslim character in a film and critiqued the anti-Pakistani politics of Indian Premier League (IPL) – Hindutva activists target SRK’s suburban Bombay home, Mannat, with massive demonstrations (See the earlier Part II for more).[1]